Have you ever looked at a beautiful little mews house in London and thought “it must be so amazing to live there?”

If so, you’re not the only one. But for the people who actually do live in those homes, social media photography has changed what it means to live in a picturesque place.

Alice Johnston is a longtime resident of Notting Hill, the London neighborhood famous for pastel-painted row houses and for being the setting of the Julia Roberts/Hugh Grant movie of the same name.

Johnston, a journalist, has complicated feelings about her Instagram-beloved ‘hood. She lives on Portobello Road, one of the capital’s most famous streets, and has witnessed all kinds of crazy behavior committed in the pursuit of the perfect snapshot.

Once, she and a friend were walking his French bulldog when a tourist asked if they could “borrow” the pup for a quick photo op. The friend and the dog consented, the Instagrammer posed with the Frenchie in front of a bright blue door and then handed over five pounds as a thank you.

Private lives, public places

In that story, everybody had a good time.

But there can be a darker side to living inside what some people think is a movie set.

“I was once woken up at 6 a.m. on Easter Sunday by French teenagers taking pictures outside,” Johnston says.

She shares another anecdote: “One time I was changing after I got out of the shower and there was this elderly man taking a picture (of my windows) with an iPad.”

Although the shutters were closed at the time, she was understandably rattled by the experience.

When private homes – and the people who live in them – become tourist attractions, clashes can occur. In more rural areas, people can put up fences or other barriers to access, but when these private homes are on public streets in some of the world’s busiest cities, what’s a resident to do?

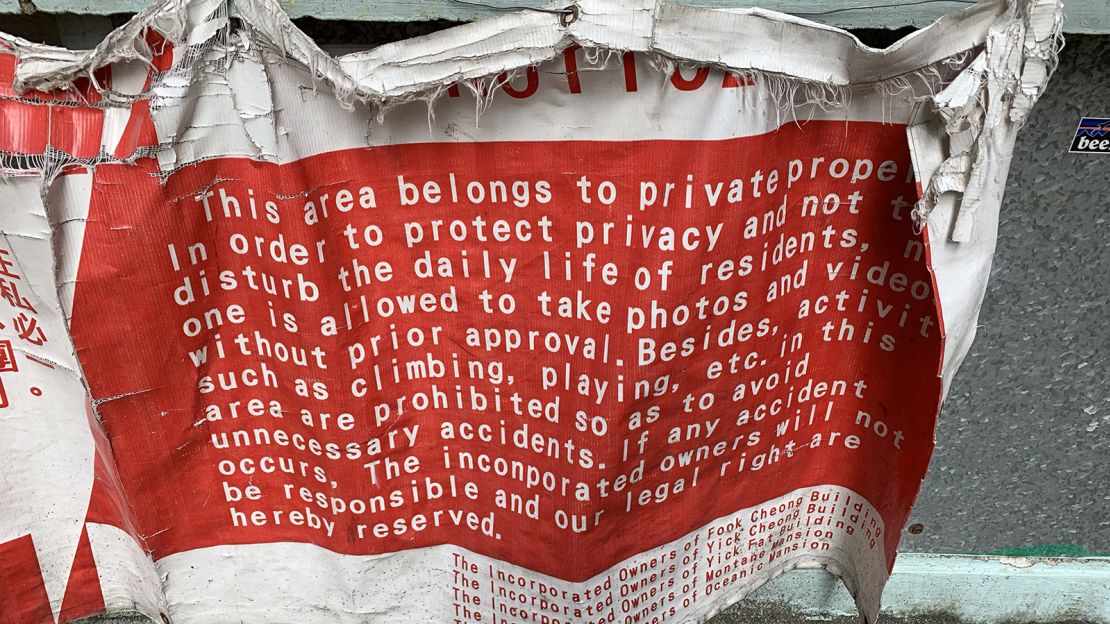

Different communities have taken different approaches. In Hong Kong, a group of five interconnected housing estates nicknamed “the Monster Building” became a huge selfie spot after it was featured in several Hollywood films, including “Transformers: Age of Extinction.”

The mega-building is in Quarry Bay, a relatively quiet neighborhood on the eastern side of Hong Kong island that most travelers skip over.

Residents of the working-class community are not able to block the building off due to the fact that there are public businesses on the ground floors. Therefore, some have taken things into their own hands by posting signs asking visitors to be respectful.

A sign in English and Chinese erected by building residents reads “This is a private estate Trespassers are strictly prohibited from all kinds of activities (including but not limited to photographing, gatherings, use of drones and yelling e.t.c.). We shall not take responsibility for property damage and/or personal injury caused by any accident.”

However, many visitors ignore the signs or simply think of them as suggestions, and a quick scan of Instagram shows plenty of recent images taken there.

Johnston says that a pale-pink house near where she lives has become such a popular photo site that the residents have given up on trying to keep people away. Instead, they’ve put up a donation box asking people to contribute money to charity in exchange for snapping a photo.

When your home is a piece of history

Chuck Henderson’s grandmother, Della, was a lover of architecture – so much that she was able to commission a home in California built by the world-renowned American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Mrs. Clinton Walker House in Carmel-by-the-Sea, nicknamed “the Cabin on the Rocks,” was completed in 1951 and passed into the hands of Henderson and some of his relatives when Walker died. No one lives in it full time, but the different family members and their guests take turns staying there.

Wright fans will come from all over the world to try and get glimpses of some of his masterpieces. While some, like the famous Fallingwater house in Pennsylvania, are year-round attractions, others remain private residences.

Many people who own homes featured in architecture textbooks have to add the cost of security measures onto other expenses like utilities and homeowners insurance.

“We put these security cameras in after we had some vandalism about six or seven years ago,” Henderson says. The vandalism in question wasn’t graffiti, though.

He explains: “We have this big wooden remnant of a tree that is placed as the centerpiece of the garden by the original landscape designer. Someone cut a notch from it. It looked clean, like someone used a chainsaw or something. One of our doors – between the carport and the main house – has a bunch of nautical cork discs in a rope net and is the counterweight for the door. That has been absconded with a couple of times.”

Stlll, though, Henderson and his family have the last laugh on the cork disc thieves – those weren’t designed by Wright and are of little, if any, value.

“We have people go walking right by the ‘private property, no trespassing’ sign. We’ve had people dancing in our carport. We get a few people wandering up as a surprise, and as long as they don’t do anything wrong we don’t try to call the police. We’re on a beach surrounded by road and don’t have a lawn, but we had a family of deer.”

Coming to a compromise

When it comes to living in a much-photographed place, some people try to take the good with the bad.

Johnston tries to be sympathetic to travelers coming to her hometown, recalling how she loved taking pictures of historic neighborhoods like the Marais in Paris and Alfama in Lisbon.

In fact, she recently found photos of herself as a teenager hanging out at the Notting Hill Carnival, years before she moved to the capital herself.

“I love to travel, so I have to be pretty understanding when people travel to where I live, and i feel lucky that it’s cool enough that people want to come where I live.”

Henderson and his relatives have come to some compromises in order to let design buffs explore the home while also maintaining their privacy. They occasionally rent it out for photo shoots, such as a campaign by eyewear brand Oliver Peoples.

In addition, they open the home to the public one day a year to benefit the local Carmel Heritage Society. In 2021, 657 people came bought tickets and toured the property.

“For us it’s a tremendous pleasure to be able to share the house and see so many people happy and excited about it,” says Henderson. “And it allows us to be able to tell people when it is open. It gives them an option (to visit) and we don’t have to be the Grinch.”

Still, it’s not clear if anyone in the family changed their minds about looking after such a high-profile residence. Henderson and his relatives sold the house in 2023.